| |

| |

|

| Home |

| |

|

"A gloriously hilarious account of what fun

playing wargames is."

The Times

"A funny, perceptive book that has you laughing throughout with

guilty recognition."

The Sunday Times

"A spiffing, biffing book that will reload memory banks of generations

of kids."

Scotland on Sunday

An extract from the book is given below.

|

|

|

| |

"A few years ago I met up with a wargamer called Dave (50%

of all wargamers are called Dave - it's the law) who was buying

some figures from me. I arranged to meet him in a branch of

Café Nero, which, as he pointed out, had lettering

on the fascia that made it look like Café Nerd and

was therefore very suitable. Dave said he had been accumulating

figures for years without any specific purpose. Box files of

them were currently providing extra insulation in his loft.

Like me he never took stock of what figures he had. I said,

maybe if he did he'd realise he had too many figures. He said

that he felt that was impossible because: "you can never

have too much of something you didn't need in the first place".

I realised at once that this was a life-changing aphorism. Though

whether it changed my life for good or ill I was no longer sure.

Most of the time the Little Men brought a ray of happiness into

my life. Often when I was working and struggling for an idea

or the final paragraph of a newspaper column I'd get up from

my desk and go and pull open a drawer at random and inspect

the contents. It didn't matter what was in it (though I knew

before I opened them because all the drawers were labelled.

I know, I know, but when you've accumulated 10,000 toy soldiers

it's a bit late to start worrying about being anal). Whether

it was lowly French line infantry or mighty Carthaginian elephants

the sight of the glittering, brightly coloured figures always

cheered me up.

At other moments though the little men oppressed me. A friend

who was reading Bob Woodward's book about the launching of the

Second Gulf War, Plan of Attack said, "The logistics of

it are mind-boggling. Before they could ship out all the food

they'd need in the desert they had sink re-enforced concrete

piles to support the platforms they store it on, because it

was so heavy if they'd just put it down on the ground it would

have sunk into the sand and disappeared. Can you imagine having

to think of all that?" Well, actually I could.

My figures needed organising into regiments, painting, varnishing,

gluing on to bases; officers and missing figures needed to be

found; they had to have terrain to manoeuvre over, hills to

march up, woods to hide in, rivers to ford, houses to shelter

behind; they had to have somewhere to be safely stored away

so they wouldn't get caked with dust or attacked by the moisture

that could spark oxidation. They needed rules and regulations

for how fast they could move, how far they could fire, how well

they could fight and how much of a buffeting they'd put up with

before they turned and ran back to the safety of their box files.

They needed generals. They needed flags. They needed two more

chariots to complete the Pharoah's royal squadron. They craved

attention like a phalanx of toddlers.

I lay in bed at night fretting about how I would ever finish

them, where I would keep them and how I would find the money

to pay for everything. War, as Woodward makes plain, is an expensive

business. Little Wars were a little expensive too. In the mid-1990s

I had sold off all the wargame armies I had spent the previous

decade accumulating in favour of collecting figures that had

been designed before 1972 and were now out of production. There

were a number of reasons for this: I liked the early wargame

figures better than the ones that came later. The later figures

had hands and heads that were disproportionately large, modern

figure designers, like modern artists having tired of mere figurative

realism. The old figures were smaller, better proportioned.

They had charm, they had nostalgia and. like all toy soldiers,

they would accumulate value the older they became.

The rarity of these veteran figures would, I stupidly imagined,

limit my spending and simultaneously nurture a nest egg for

my retirement. The trouble was that whereas before I could put

off buying figures that I saw for sale safe in the knowledge

that they would still be available next week, next month or

next year, now I no longer could. Now every batch of 1968 Hinton

Hunt 20mm Norman knights, or 1963 Stadden 1/72nd Crimean war

Russian Infantry (in greatcoats), advancing at high porte that

came up on eBay, or appeared in the classified ads in Wargames

Illustrated, Miniature Wargames, Military Modelling, or Military

Modelcraft was a one off, unrepeatable chance of a lifetime.

When I got them I experienced a wild buzz much as the gambler

gets when he wins a big bet. And when I didn't I was seized

with the collector's nightmare - a vision of the decades of

regret and bitter recrimination that would follow as I slowly

realised that such an opportunity would never, ever present

itself again. A mania born of terror and desire gripped me.

Unlike governments I couldn't raise taxes, so I made cuts. I'd

already given up smoking to spend the money I saved on figures

instead. This was a fine idea. And frankly it was as well I

stuck to it. Because if I'd spent the same amount of cash on

tobacco I've since spent on little lead men I'd be talking through

a hole in my neck. Now I went into overdrive. I sold

a collection of 1960s cycling books and bought French Cuirassiers,

200 vinyl LPs furnished a small English Civil War army, 50 picture

sleeve punk singles bolstered the exotic ranks of the Great

King of Persia, a Schuco clockwork grand prix racer bought on

my first trip to London when I was ten contributed to raising

a division of Bavarian infantry, four Revel 1/32nd scale slot

cars recruited a couple of boxes of Samurai. I felt as if all

the lead I had handled, carved and inhaled had given me lead

fever. Day after day the postman struggled up the drive, back

bowed and knees buckling under the weight of the parcels. Ancient

Indians came from Maine, North West Frontier Tribesmen from

Baden, Carthaginians from Ohio, Spartans from New Zealand. I

sold and I bought. My bank statements and my credit card bills

suggested I had put our domestic economy on a total war footing.

Soon my finances had begun to look like Brandenburg after the

Thirty Years War, broken, charred and apparently incapable of

sustaining life now or in the future.

"Who buys a minute to wail a week? Or sells eternity to

buy a toy?" I knew the answer to Shakespeare's question.

It was staring back at me every time I looked in the bathroom

mirror. I felt as if I was caught in a miniaturised maelstrom,

spinning towards insanity and ruin.

As I lay awake at night, my mind filled with the incessant demands

of my lead armies, I began to wonder who was in charge: me,

or them? I owned them and yet somehow I had become their captive.

Some times I wondered how it had got this way. And some times,

like Burt Lancaster in The Sweet Smell of Success, I wished

I wore a hearing aid, so I could switch off the babble of the

little men.

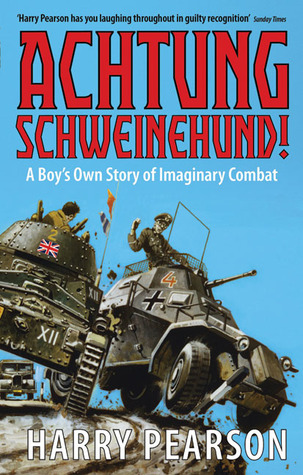

Achtung Scheinehund! A Boy's Own Story of Imaginary Combat by

Harry Pearson

Published by Little, Brown 2007. ISBN: 978-0-316-86136-6

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| The site

has been created by Richard

Black and Harry

Pearson |

|